- Home

- Kim Paffenroth

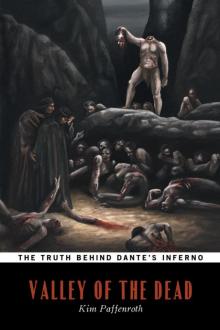

Valley of the Dead (The Truth Behind Dante's Inferno) Page 2

Valley of the Dead (The Truth Behind Dante's Inferno) Read online

Page 2

He dismounted as she got closer, and although he didn’t yet raise his sword, he held it ready, wary even of a woman in this strange place. She stopped a little distance away and eyed him, panting. She looked over her shoulder. Dante followed her gaze and saw one of the unarmed men had spotted them. He trudged toward them. He must have been injured, for he walked slowly and stiffly, as though it caused him pain.

The pregnant woman looked back to Dante. “We have to go, sir.”

He had ridden for days in a generally southeast direction from Budapest, and he really had no idea what tribe or clan he was among at this point. But he knew he was nowhere near Italy or any other civilized race, so he was shocked to hear something he could decipher as a language somewhere between Latin and Italian. The vowel sounds she made were different than he was used to hearing, and the endings of the words were not quite like either Italian or Latin, but he could understand her. Even given their dire and violent situation, he couldn’t help but ask, “You speak Italian?”

“What? No, sir.” She again looked over her shoulder. “The horses are all gone. You have to take me, sir. I can’t outrun them forever. Not like I am. And now the army has come, we’ll all die.”

She turned and moved closer to Dante, so they both stood facing the unarmed man who continued walking toward them. Still eyeing the woman’s bloody piece of firewood, Dante turned his attention to the man. He could see his mouth hung open, and both his arms were bloody, together with much of his torso. He favored his one leg and all his movements seemed strained, forced, unnatural. Dante now realized the constant moaning he heard came from this man and some of the others. He was making an animal sound continuously, as he kept his vacant eyes fixed on the woman. Dante raised his sword. “Stop.” His voice sounded small, polite, and impotent through the din of the moaning and battle. “Leave her alone.”

The man showed no interest in him, no fear at his blade, no recognition even, but kept all his attention on the woman. He shuffled toward her and raised his arms, as if to grab her. Dante took a step and thrust his blade into the man’s chest, then withdrew it. Although there was dried blood all over him, this new wound didn’t bleed fresh. The man didn’t flinch. It had been a good attack, a stab in the region of the man’s heart that had gone clean through to his back. He should have gone down immediately, dead or at least unable to breathe and on the brink of death, but he showed no signs of noticing the wound whatsoever.

“What are you doing?” the woman shouted. “Don’t you know how to fight them?”

The man was nearly on her as she raised her club in both hands. With a shriek she brought it down on his head. He staggered back, his eyes rolling upward, his jaw dropping more. She pulled the club back over her right shoulder, still holding it with both hands, and delivered another blow, this one to the side of his head. It made him stagger, turn, and fall to the ground, facedown. She’d swung so hard it threw her off balance and spun her more than halfway around. The man didn’t seem able to get up, but his left leg still twitched, and his hands clawed weakly at the ground, even though any of the three blows he just took from sword and club should have been enough to kill him. Then, like the men Dante had earlier seen savaging those who had fallen, the woman stood astride the man’s back and brought the club down four more times on the back of his skull. Dante couldn’t move or speak as he watched her reduce his head to a pile of hair, blood, brain, and bone that spread out in an irregular splotch on the ground. His leg and hands didn’t move anymore.

The woman dropped her club next to the body as she stood up. Two more unarmed men were now approaching them. “Sir, now, we have to go,” she said between ragged pants, breathing harder than before. “We can maybe fight off some of the strigoi, but if any of the men of the town see us, they’ll kill us to get the horse and escape themselves.” Dante didn’t understand the word she’d used, strigoi. It was very close to the Italian word for “witches,” but that made no sense. The woman stepped away from the corpse and toward Dante. “My husband and son are dead. You have to help me, sir. I can’t do it alone.”

He hesitated, as another projectile crashed into a house and erupted. The smoke and heat were building around them, stinging his eyes. He looked from the approaching men, to the grisly pile of flesh on the ground nearby, to the panting, sweating woman right next to him. Dante was a worldly man and had seen his fair share of the weird, the violent, and the senseless, but he had no way of comprehending any of the horrors happening around him. As he looked down at the woman, he caught the rank smell of her sweat, and it was the first reassuring thing he had sensed since the silence of the day had been shattered minutes before. Of course, she smelled terrified and profane, like the animal she had just shown herself to be. But mostly she smelled alive – and more importantly, like something that was supposed to be alive, something with a purpose or reason to exist, unlike everything else around them, which seemed like random chaos existing only as the negation of everything true and real.

He stepped past her as he sheathed his sword. He put his right foot in the stirrup and swung up on to the horse’s back, then leaned down to extend his hand to her.

“Come,” he said.

With difficulty she climbed up behind him. Dante had seen women sitting astride a horse before, but it still surprised him when she swung her left leg to the other side of the horse. Proper women didn’t ride that way, and especially not with their legs on either side of a strange man; but proper women didn’t beat men to death, either, so there were other things to consider at the moment. He pulled the reins to the left, and started the horse trotting away.

As the sounds of panic and death receded, Dante asked her, “Which way?”

“Into the woods, sir” she said, pointing off toward the woods Dante had seen on the other side of the road before discovering her besieged village. “The army probably cut off the road in either direction to kill anyone trying to escape. In the woods we can head towards the mountains. Perhaps it’ll be harder for the troops or the strigoi to follow us. Perhaps we might survive.”

Dante still didn’t know what she was talking about, either in terms of whose army this was, or what she meant by strigoi, but now was not the time to ask. He pulled the reins and pointed the horse toward the trees. As they moved under the canopy, it did feel safer in the shadows. The woman’s arms around his waist tightened. As improper as it was, it definitely felt better and safer than anything he’d experienced in years.

“And what will we do when we reach the mountains?”

Her head rested on his shoulder. “Go over them, I suppose.”

“And what’s on the other side?”

“I have no idea.”

“No idea, and yet you choose to go forward? You are a woman of great faith, then?”

“Sir, there are hundreds of men and monsters trying to kill me. Why would the unknown frighten me? I must either have faith, or else sit down, curse God, and die. I’m not ready to do that.”

Her swollen belly was pressed up against his lower back. It did not feel soft, compliant, and sensual, the way a woman’s body usually did, the way he thought a woman’s body was supposed to feel. Instead, it was hard, insistent, resolute. And Dante felt sure that, like all women, she was much more aware of her body and the signals it was sending than a man ever could be.

“I understand,” was all he could say to her as the horse picked its way between the trees and they went deeper into the silent shadows.

Chapter 3

“Her eyes were shining brighter than the Star;

And she began to say, gentle and low,

With voice angelical, in her own language…”

Dante, Inferno, 2.55-57

In a few hours they were far into the forest, embraced by its grim simplicity and, for the time being, insulated from all the madness of men and death. Before it got too dark, Dante stopped in a small clearing, tethering his horse and letting it graze on the grass. The woman helped him gather wood to build

a fire. It was sure to be cold in the night, and the flames would keep wild animals at bay. She gathered mushrooms, some early berries, and nuts to help supplement their meager rations. There was a small stream nearby for water as well, its water icy, clear, and in some spots, deep.

While they were busy gathering wood, Dante studied her. Given their odd situation, he did so as discreetly as possible, out of respect. Even though she was of a much lower social class than he, Dante felt he had no right to judge or demean her. Dante’s eye for detail – especially details related to beautiful, young women – was refined and acute enough that a few glances at her told him a great deal, put her into a context that related her both to this unknown, barbaric land into which he’d fallen, and compared her to things more familiar to him.

She was exceptionally thin and lithe – a small framed woman carrying no extra weight except what her pregnancy had put on her. Her arms were sinewy and, through the rips in her blouse, Dante could see the taut muscles of her back. He shivered when he remembered her savagery as she had killed the man. There was no doubt of her physical strength, or her determination to use it. Her face, on the other hand, was cherubic, probably from being pregnant, and with girlish features – small, dark brown eyes and long, thick, brown hair. She had dimples in her cheeks and her chin, an upturned nose, and a wide, thin-lipped mouth. She was clearly young, but Dante remembered she’d mentioned another son, so this wasn’t her first child. She was probably in her late teens or early twenties.

Dante felt chilled then flushed when he realized she was about the same age as Beatrice was the second time he saw her in Florence, the time she had actually spoken to him and thoroughly enthralled him. He allowed himself a small, grateful smile for being granted such glimpses of feminine perfection. This woman seemed so much more physical and primal than Beatrice had been on the sunny streets of Florence, while Beatrice had seemed completely spiritual and sublime, compared to this sweating peasant in a dark forest. But at that moment it made no difference to him, filling him with awe at them both. As different as the two women clearly were, Dante knew there was something in both that made him want to serve them, earn their respect and affection, live up to his potential as a man. They had within themselves not merely the object of a man’s desire, but the lure and hook that could draw him to desire something more, better, and higher than either them or himself, the same way the sun drew the tendrils of a plant upward, kept it alive, and filled it with the vital force to produce another of its kind.

The thought moved Dante from a small smile to a slight frown. He had never lived up to Beatrice, so why should today be any different? After seeing her a second time, he’d been inspired to write a poem about her. He’d called it The New Life, but his life had hardly been revived or improved by his writing it. In his mind he remained a weak, inconstant, and, most of all, petty and inconsequential man. The poem had only been a trifle, and he should have long ago exceeded it in beauty and depth, producing something worthy of Beatrice and the Lord she had served so much better and virtuously than he did. While he’d taken so long writing such a little, unimportant book, she had died, both of them already having married other, more suitable people. If in his comfortable, privileged, easy existence in Florence he had not been able to accomplish something great, beautiful, and heroic, how dare he think he might do something worthwhile for this poor woman here today, in this savage, deadly land? He could barely hope to save himself, let alone her.

Before they sat down by the fire they had built, Dante got a jacket out of the saddle bag and offered it to her. “Your blouse,” he said, “it’s torn. Put this on.” The coarse, woolen, reddish-brown frock he always wore would be adequate for him, but modesty and practicality both called for something more for the woman, especially in her condition.

Without the danger and urgency of the deadly attack when they had first met, she now seemed acutely aware of the awkwardness of their situation, and the difference in their social standing. She blushed and looked down as she took the jacket from him. “Thank you, sir.”

They sat down to eat the food she’d found, together with some bread and dried fruit he got out of the saddle bags. She didn’t make eye contact, and sat on the opposite side of the fire.

Dante realized he still didn’t know her name, so he asked her.

“Bogdana,” she said, still looking down.

Dante nodded and restrained his grimace at such an ugly name, in case she did look his way. It was surely a further indication of the barbarity of this place--that anyone could even think to place such a discordant, three-syllable monstrosity on to such a beautiful creature. Back in Italy they gave better, more mellifluous names to types of pasta, or rodents, or even insects. “Beatrice” sounded exactly like what the person so named really was – a blessed person, a blessing to others. “Bogdana” sounded like some curse spat out when one stubbed one’s toe or was gripped by an acute stomach cramp.

“What does this name mean?” he asked her.

“Gift of God, sir.”

Dante continued to nod. Why quibble with the sounds and limitations of fleshly tongues and ears, if the meaning were so right and true? After all, many blamed and mocked him for writing in Italian rather than Latin, for they thought his native language – even when it was the same as theirs! – was somehow low, vulgar, base. He would have to work on keeping that in mind when he spoke or thought of her.

“My name is Dante Alighieri.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Please, enough with the ‘sir.’ It’s not necessary. We’re here, trying to survive. There’s no need to follow such rules. Is that all right?”

“Yes.” She faltered and left it at that.

“I still don’t understand what language you’re speaking, why we can communicate, if you don’t know Italian?”

She looked up and shrugged. “I don’t know either. I speak what I’ve always spoken, what I learned as a child. I don’t know why it’s similar to your language.”

“What is this place called?”

She finally met his gaze fully and again shrugged. “To the west is Hungary. Some say we belong to their kingdom. Some say we are Moldavians and should unite with other nearby people. We have always called ourselves Romani. I do not know what you would call us.”

Dante thought perhaps “Romani” was a clue that the people here remembered, however inchoately and indistinctly, that they and their language were descended from Roman invaders, long ago. There was no way to check the theory. They would just have to accept that it made their present situation much easier, since they could communicate.

“But who is your king, your monarch? Who sent those troops that were attacking your village?”

“We have no king, if you mean someone who rules this whole land in all directions for many days’ journey. Here there are just local rulers, boyars, who rule their little parts of the country. The boyar must’ve sent troops to destroy our village, or perhaps the plague is so widespread that several boyars banded together to attack us.”

Just as Bogdana’s name seemed oddly incongruent, Dante thought that word, boyar, sounded a good deal more gentle and peaceful than what he had witnessed the boyar’s men doing back at the village.

“Some people must have fled our village when the strigoi attacked. They must’ve gone to the city and asked for help. But when the monsters attack, the only help is for troops to come in and wipe out the whole area. They should’ve known that and stayed with us to fight. We would’ve had a better chance than we do now, with both the army and the strigoi after us.”

“You keep saying that word--strigoi. It must be different between our languages, because the only word I can think of in my language that sounds like that means ‘witch,’ a person who uses bad magic.”

Bogdana smiled. “Yes, people used to think the strigoi were magic, some evil spirits or cursed, sinful people. But that’s just superstition and nonsense. They are a disease, a plague. They are simply the dead, who rise up a

nd kill the living.” She lowered her voice. “And eat them.” She raised her eyebrows. “You have never heard of this before?”

Dante shook his head. “No, never. I have never heard of such a thing anywhere else I have traveled.”

She nodded. “Well, that is a good thing, I suppose. They are a curse only to us, and the rest of the world is spared. Well, good for you all. Not so good for us. And not so good for you and me today.”

“So the man you killed back at the village, you’re saying he was already dead?” Dante could not hide the relief in his voice. It was much more palpable than the shock and wonder at speaking of a dead man being killed a second time.

“Yes, he was my neighbor. I knew him. I could never do such a thing to a living man!” She lowered her eyebrows and a hint of a glare rose in her cheeks and eyes. “What kind of monster do you think I am?”

“Oh, no, I didn’t mean anything like that,” he stammered. “I’m sorry. I’ve never heard of walking dead people. I was just surprised.”

Bogdana’s eyebrows rose again and she looked less angry. “Well, I suppose, since you’d never seen the living dead before, you were confused. But, make no mistake, Romani are no different than you. We raise our children and tend our crops and, when we can, we bury our dead and mourn them. But when the plague strikes and the dead walk, we do the same as you would. We fight them any way we can in order to survive.”

“I understand.” He found himself saying that to her once more, and thought he did understand her, better than he had anyone for some time. She was simple and unadorned, unashamed and without guile. More than love or attraction, he felt mostly gratitude for being allowed to meet her. “You said your family was killed?”

Life Sentence

Life Sentence Valley of the Dead (The Truth Behind Dante's Inferno)

Valley of the Dead (The Truth Behind Dante's Inferno) Dying to Live: Last Rites

Dying to Live: Last Rites Dying to Live

Dying to Live